Transcription can be found below

l

l

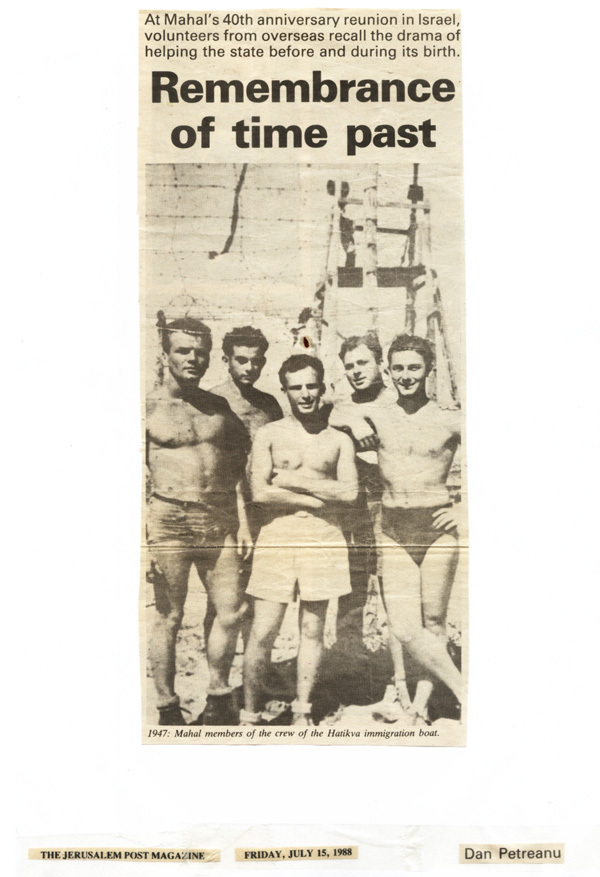

At Mahal’s 40th anniversary reunion in Israel

Volunteers from overseas recall the drama of

Helping the state before and during its birth.

Remembrance of time past

Forty years ago, the Mahal foreign volunteers in the War of Independence were bonded to the country. Some of them have been touring this past fortnight. One night this week, in the lobby of the Carlton Hotel in Tel Aviv, they traded war stories with a vigour normally associated with younger men. The same vigour glowed from the pictures that changed hands all night.

“That’s Murray Aronoff, on board the Exodus, where he was wounded”, says Murray Aronoff, pointing to a photograph of a tall young man with a bandage around his head. Quickly, another picture is produced. “And this is Murray Aronoff’s old man, who fought in the World War I Jewish Legion”, he adds.

His soft eyes glaze somewhat, and his gruff voice cracks when he mentions the “old man”. It was perhaps to emulate him that the sturdy 20 year old, who was not drafted in World War II because he had polio, volunteered in 1946 for Aliya Bet, the “illegal” immigration operation.

“The story’s been told many times, says Aronoff. On the Exodus, which was his first mission, he was placed in charge of a squad of about 50 mostly Moroccan Jews who served as an internal police force. “There was a lot of policing work to be done on the ship” he recalls. “The Exodus, with 4,559 people on board, was very crowded. Tempers ran short, people shoved each other around, and so forth”.

But his adventure came to an end on July 18, 1947, when the British boarded the Exodus several miles off the coast of Palestine. In the 10-hour battle, Aronoff suffered head injuries and was taken to France aboard a prison ship. After a month in a French hospital, he returned to the U.S. and became a fuknd-raiser for the United Jewish Appeal.

A few months later Aronoff volunteered for another “illegal” immigration mission, on the Galila. This time, he did not encounter resistance and landed on Israel’s shores at the end of May 1948. “We didn’t make it in time for the Declaration of Independence”, he says, “but we gave Israel 1,200 of its first immigrants”.

Since then, back in the U.S. the divorced father of five has been active with the UJA. He is also chairman of the Mahal organization, American Veterans of Israel. His dream for the past three years has been to erect “a living monument” to the Mahal in Moshav Avihail, where it current occupies a wing of the Beit Hagdudim museum.

“I’m thinking of something along the lines of a rest home for wounded soldiers, with only a few rooms actually being a museum”, he says.

Aronoff also hopes to set up a worldwide Mahal organization. He is amused by attempts to phrase inquiries delicately on what would be the point, given the veterans’ age.

“My answer is always ‘We’re not dead yet’”, he says, smiling.

Aronoff is unapologetic about not having lived in Israel. “The Jews are a people of the Diaspora. They always go to the affluent countries”, he says. “To me, the Jewish state and Jewish survival are the same thing. If I contribute to one I’ve contributed to the other, regardless of where I do it”.

Joe Landow, 77, the man who organized the Mahal 40th anniversary reunion here, in 1949 acquired “the first uniforms of the first Jewish army in 2,000 years”. He regrets having left Israel a year later to return to a career in the KU.S. in tax law and financial planning. He had been a major in the U.S. Army in World War II, serving in staff positions under General Dwight Eisenhower and Lucius Clay. During 1948 e neglected his career as an accountant and attorney, devoting much of his energies to helping Teddy Kolek’s Israel Supply Mission circumvent the American arms and equipment embargo on Israel.

Landow and his staff of Jewish World War II veterans raised money in “parlour meetings” with wealthy Jews, and helped send the Israeli army supplies such as “tents, shoes, raincoats, and even guns the Jewish veterans brought back from Europe as souvenirs”. In October 1948 he was persuaded to come to Israel and join Aluf Yosef Avidar in handling the logistics problem of the IDF. “I went to various fronts, prepared reports on logistics problems, army organization and other matters which drew on my previous staff experience”, he says.

But Landow’s day in the sun came after the fighting was over. “Until that time, soldiers used to wear anything and everything” he explains. “But after the war, uniforms became a very urgent necessity”.

Thus, in January 1949, Joe Landow was summoned to Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s office and entrusted with the acquisition of uniforms before Independence Day, only some months away. “A small man would have given me the chance to cry on his shoulder”, says Landow. But not Ben-Gurion. “The old man was not interested in excuses – he only wanted the job done”.

So Landow rushed to New York where, after more parlour meetings, he succeeded in raising the money to buy several hundred thousand American uniforms, which were shipped to Israel and given Israeli markings.

“A crucial issue was size” he recalls. “I had noticed that sabras tended to be large and strapping, and Holocaust survivors and Jews from Arab countries tended to be small. Sincere there were relatively few people in between, I purchased mostly extreme size uniforms”.

He returned to Israel with his wife and two children that June and working with Aluf Haim Laskow, set up a plan for a Defence Ministry comptroller.

“But despite the fact that we were given an apartment and I was offered other permanent positions, by May 1950 my wife decided that she wanted to return to the States”, says Landow. “It was a very painful decision for me”.

True to his nickname, the only man in the lobby wearing shorts is 72 year old Irvin “Swifty” Schindler. A retired airline pilot, he is today mainly a collector of antiques. Nothing about Swifty would lead one to suspect that 40 years ago he was the key to the airlift that brought Israel the arms, without which it would have stood a very small chance of surviving the War of Independence.

“Ever since Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic, I knew I wanted to be a pilot” he says. He took flying lessons and in 1941 was abel to get a job with the company that eventually became American Airlines. After the war, along with a partner, he set up a small aviation company called Service Airways, whose two small twin-engine planes initially flew mostly transport missions to Central America. During this time, he also piloted transatlantic flights with other companies.

In February 1947, Schindler was approached by men posing as Hassidic Jews and asked to estimate the cost of conducting illegal immigration operations by plane. Although it turned out to be too high, this led to contact with the “Materials for Palestine” operation, which needed planes to fly supplies in preparation for the imminent war with the Arabs.

They gave him the money to buy a number of small planes and he began to train Jewish pilots. The American embargo against Israel in 1948 complicated his plans immeasurably. When a failed attempt to set up a base in Italy attracted the attention of the FBI, Schindler was forced to move his base of operations to Venezuela, where for three weeks his company was in effect the first Venezuelan airline. In May 1948, his 10 small transport planes reached Czechoslovakia, and from there he conducted what he estimated to be 98% of the airlift of arms to Israel.

“This included the transport of munitions, jeeps, and 12 dismantled Messerschmidt aircraft” he recalls.

Later that year, Schindler return to America to take part in a plan to acquire combat aircraft. “Unfortunately, the FBI interfered, and only one of the four B-17 bombers made it to the meeting point at the airport in Westchester County” he says. Nevertheless, he managed to get the one plane off the ground, but fuel difficulties forced him to land in Halifax, where he was arrested by Canadian Mounties.

“We then received an order to return to New York or Boston, but I delayed the trip till night and managed to evade our American escort plane back in the dark”. But the fuel problem continued, and the B-17 only got as far as the Azores, where Schindler was again arrested, and dispatched to the U.S./ there, he pleaded guilty to “the illegal export of planes”. His light sentence of one year’s probably was “somehow arranged”.

“But it was the end of my career”, he says sadly.

As Zionists, the Mahal volunteers are something of a paradox, admits Mahalnik Victor Perry. In a sense, they appear to embody much of what Zionism hoped to unleash in the Jewish people – a sense of adventure, a willingness to sacrifice, a desire to contribute to the return to Zion.

Furthermore, most of them were not ragged fugitives, but volunteers from relatively wealthy countries, risking what in many cases promised to be prosperous and comfortable lives. They were the sort of people whose presence here seemed to prove that Israel was necessary not just as a refuge, but as a true national home.

But only 10% established permanent residence here. Observing the representatives of the other 90% in the elegant Carlton Hotel lounge, the question inevitably presents itself: How did Israel fail to attract these motivated men of all people?

“Aliyah was probably not much of an issue for most of them”, says Victor Perry, a Mahal pilot who remained in Israel. Perry can recall some reasons cited by individual Mahalniks who left, but the real reason, he says, is that “they came here not to settle but simply to defend an idea they believed in”.

Gordon Levett is astonished that more people, especial non-Jews, didn’t come to Israel’s defence in 1948.

“Israel was the best cause in the world after the Holocaust”, says the 67-year old Christian. “There is only one reason why people didn’t volunteer to come here in the numbers you saw during the Spanish Civil War – damn f—ing anti-Semitism”.

In 1948, the former RAF Spitfire pilot volunteered to fly missions for Israel. “I thought the British policy of now allowing in the survivors of Auschwitz was a crime”, he says. “I suppose I came in order to compensate Israel for what the British had done”.

During the war, Levett flew more than 20 sorties with the nascent Air Force’s 101 Squadron. “The composition of the squadron was very ironic”, he says, recalling the American Mustangs, British Spitfires, and German Messerschmidts transporting by Swifty Schindler. From one of them, Levett shot down two Egyptian Spitfires.

In early 1949, levett was a pilot in the 106 Squadron, which conducted the airlift that enabled the capture of Umm Rashrash – today known as Eilat.

“Bernadotte wanted to give the Negev to the Arabs, and the Jordanians were already making moves towards the region”, he remembers. “But in a very short order we succeeded in doubling the size of the country without a single drop of bloodshed or shot fired”.

After the war was over, levett says, he had no desire to go back to “grey, cold England”. Neither, however, did he want to convert to Judaism and remain in Israel. “People would have said I was only looking for a job”. So in the end, like the overwhelming majority of his fellow Mahalniks, he returned home.

“I don’t see why you had to be Jewish to support Israel”, he says. He sips his beer and surveys his old comrades. “It was a good enough cause for all of us here to support”.

But there is a difference between levett and the others in the lounge. AS he tells his story, completely without emotion, it is plain that he is at peace with himself.

He has given Israel more than it has a right to expect.