EXCERPT FROM

“A TEENAGER IN HITLER’S DEATH CAMPS”

BY BENNY GRUNFELD

“IN ISRAEL, 1948-1952”

Benny Grunfeld was born in Cluj in Romania in 1928. He survived the Bergen-Belsen camp with his brother, Herman, who was four years older than he was, and went to Sweden after his liberation in April 1945.

EXCERPT FROM BENNY’S BOOK

In the summer of 1948 I read in the newspaper that former Nazis had enlisted as volunteers on the Arab side in the war against the newly established State of Israel. This information aggravated me so much that I asked the Swedish Zionist Association to help me enlist as a volunteer in the war between Israel and the Arab countries. I assumed that the Israelis wanted as many soldiers as they could get. Confirming that reinforcements were sorely needed, they said that I could count on leaving within fourteen days and that they would soon contact me with further details.

The notice of departure came more quickly than I had expected. Though I had an alien’s passport, invalid for re-entry into Sweden, I didn’t plan to stay in Israel forever. I would have preferred not to leave without permission to re-enter, but there was no time to arrange it. However, the Zionist Association promised to take care of my re-entry when the time came. Everything was ready to go. Several of my friends joined me, including one with whom I had made traffic signs for the English at Bergen-Belsen. We were thrilled to see each other again. We took the train from Stockholm to Malmo, then flew from Bulltofta to Amsterdam. Israel had bought an older passenger liner from Holland and re-christened it the “Negbah.” We weren’t scheduled to leave for Israel until a week later. With my meager savings, I bought a round-trip ticket to Brussels, where my girlfriend Eva was living with her sister and some other relatives. It was a happy time for me. But that only made it that much more painful when I had to say goodbye and return to Amsterdam. The voyage to the Israeli port of Haifa took over a week.

I now became one of roughly 4,500 Machalniks – Mitnadvei Chutz L’Aretz to use the Hebrew term, and Volunteers from Outside Israel, to use the English translation – who came to Israel and fought alongside Israel’s regular armed forces.

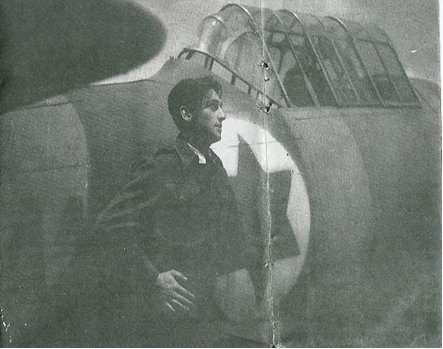

When a flurry of press photographers greeted us, we were all flattered, until we discovered that they had come to take pictures of the ocean liner. We took a bus to a military base on the outskirts of Haifa. The war was going full steam, and the city was blacked out. The next day we went to a large military base further south and received our uniforms. Several days later we went to Tel Litwinsky for training. I was assigned to the air force along with one of my friends from Sweden. After a few days at headquarters in Jaffa, we went to an air base near Rehovot, where we joined a crew comprised of several different nationalities. Most of the technicians came from the U.S., England, Sweden, and South Africa. A while later, a whole contingent of Italian technicians arrived. My commander was a big, jovial American.

During World War II, the airstrip where we worked had been a base for Liberator bombers. After bombing missions, some planes returned to base seriously damaged. Most of them ended up helter-skelter in one big pile. Plucking parts from the plane wreckage was not an entirely safe thing to do. Our job was to construct a workshop for overhauling aircraft engine accessories. We built test benches, and also performed a complete inspection of the accessory parts, which we finally repainted and tested. The most difficult job was building a test bench for the Stromberg fuel-injection carburetor. When, after a great deal of effort, we had almost finished the construction, a completed test bench arrived from the U.S.

Certain spare parts were difficult to get hold of. One episode I particularly remember involved the booster pumps (electrically-powered gasoline pumps which insured that the motor-powered gasoline pumps always had enough fuel, regardless of the plane’s position in the air) for the Spitfire attack plane. The pumps were hard to get into working condition. After a complete overhaul and subsequent testing, it turned out that they leaked. The leakage was caused by a deficient rubber seal on a metal washer. Before long the Spitfire flights had to be suspended due to a lack of adequate booster pumps. When I was at a nearby office one day, I noticed a secretary typing stencils. Whenever a key went through the stencil, she would replenish it with some kind of sealing wax. That gave me an idea. I asked if I could borrow her little bottle of sealing wax for a while. I tried it on one of the rubber seals. To my great delight I succeeded in fixing the leak. Soon we had functional booster pumps and the attack planes could fly again.

New types of planes were constantly being developed. The Israelis bought everything they could get their hands on. Before long we had to expand both staff and facilities. I made friends with a number of Swedish pilots, mechanics, and other specialists. A few of them played an important role in my life after my return to Sweden, including a legendary pilot by the name of Thorvald Andersson, who started an airline where I worked long afterwards. I got along just fine in the Israel Air Force. I learned English, a little Hebrew, and even some aircraft mechanics.

I was discharged from military duty after a year-and-a-half. I agreed to stay on as a civilian mechanic but soon began to long for Sweden. In addition, I suffered from sciatica. I applied for a re-entry visa at the embassy, but it was turned down. Then I wrote to the enlistment officer in Stockholm reminding them of their promise to help me return to Sweden. The promise turned out to be worthless. Herman was my last resort. He contacted the Aliens Commission, the forerunner of today’s Immigration Board. Though I had never done anything illegal during my stay in Sweden, they refused my application over and over again. At last Herman requested an appointment with a prominent member of the commission. They let him speak with an assistant. Herman explained that we had miraculously survived the war, lost our whole family, and felt that we had to be together. Otherwise he would close down his shop and leave Sweden. Apparently that impressed the official, because he promised to seek approval of my application at the next meeting of the commission. It took a year-and-a-half for me to obtain permission to return.

Herman sent me tickets for the boat from Haifa to Marseilles and for the train from Marseilles to Stockholm. I longed to see Paris. Since I had read so much about the city, it was fantastic actually to be there. I stayed over a week. That was all I could afford. On the train from Paris to Copenhagen, I ate the cheapest meals, and soon my money ran out completely. I was very hungry so the trip from Copenhagen to Stockholm was quite a trying experience. Somewhere along the way a group of Swedish teenagers began to unwrap the snacks they had brought along. My mouth watered and I tried to look the other way. But one of the girls asked me if I wanted to join them and I gratefully accepted some bread and butter. It felt as if I were returning to a warm-hearted family. Unfortunately I was too shy to ask for her address and telephone number. I would have liked to return her kindness.

In 1998 I was invited to Jerusalem along with all other surviving Machalniks by President Ezer Weizman. On May 4, 1998, in connection with the celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of Israel’s statehood, I was decorated by him for my services as a Machalnik in the War of Independence.

Source: Excerpt from the book written by Benny Grunfeld “A Teenager in Hitler’s Death Camps”