First published in ESRA magazine

ALTHOUGH priority was given to pilots and seasoned soldiers among the many South Africans who rushed to volunteer at the outbreak of the War of Independence, a decision was made to allow each youth movement to send representatives. I was one of six members of the Zionist Socialist Youth Movement told to pack my bags. In those days it was at least a two day journey with an overnight stay in North Africa. Before leaving we were called for briefing and issued with strict instructions: “Sit separately.” “Do not speak to each other.” “Do not let anybody know that you are together.”

Our first stop was Rhodesia and on the way I learnt what air sickness was. We had to disembark and as we boarded again, the air hostess asked me “Are all the six of you flying on to Israel?” So much for secrecy! We had to sleep over in Rome but sadly we had not been informed of that and all that George, my traveling companion, and I could afford was gelato Italiano of which we tried pretty well all the flavors. At that special meeting we were also given an address in Rome and told – “Remember the address. Do NOT keep this information on you. In a crisis you have to swallow the paper!” In Rome we boarded a bus and asked the conductor to tell us where to get off – “Ah!” he said, “So you are also going to the Israeli offices!” Duly we arrived in Israel and I traveled to Haifa seated on a Tnuva box. Today there is a dual carriageway but then there was just a narrow inland road where two vehicles could barely pass one another. Indeed one volunteer unknowingly sat with his arm out of the window – he never made it into the army! Georgie and I found ourselves conscripted into military service in spite of having no previous training.

We arrived in Tel Litwinski only to be informed that there was a four-day truce and we could have leave. I was blessed with family in Israel and so I made my way to visit, laden with gifts from my mother. I reached the family home in Petach Tikva and there found two ladies in the yard, bent over a washtub, scrubbing the laundry and nearby a little old lady was issuing orders – it was my adorable savta and my mother’s two sisters. They had not set eyes on me since I was three years old yet one of the aunts lifted her head, looked at me and exclaimed in Yiddish “Du weiss ver dos es? Dos es Yossele!” The next day I made my way to Jerusalem to see my father’s family in Rehavia. The only means of travel was in convoy. This was the home of my father’s youngest sister – I also had gifts for them and food from the family as there were food shortages in Jerusalem. My aunt had also not been informed of my coming but as she set eyes on me she shrieked “Mordechai!” – my father’s name. This surprised me as I did not look like him in the least but that is what excitement does. She had already lined up a shidduch for me with her husband’s niece! I didn’t refuse the shower they offered me and only afterwards did I learn that I had used up their week’s supply of water. I left Jerusalem the next day in the dead of night, part of a convoy that had to travel in complete darkness due to imminent danger on the Burma Road. We lost sight of the vehicles ahead and we were on our own. As dawn broke we indeed reached a town – but not the one expected. Where were we? Strange people filled the narrow streets. I was in shock but an Israeli local calmed my fears “You are in Rehovot,” he explained, “and this is the Yemenite Quarter.” The truce came to an end and I was back in Tel Litwinski. My army career was about to begin – but that is a new chapter. If you are interested in reading it please let me know.

THE four-day armistice was over. I was back in Tel Litwinski, ready to begin my army career. How long was our training period? One week? Two weeks? There wasn’t time for more. We had to be on our way. Little did we realize the commotion we would cause. We were scheduled as an artillery unit, our trucks towing the large heavy guns. True, it was sixty years ago, but as vivid as ever I remember our trip up north. As we drove through the town of Afula, people came running out of their houses – women and children. All the men were on active duty. They ran after us, touched the guns, kissed them. They had never seen anything like this. Israel was armed. They held out their lebenia, their chalot.

What else was there to offer? We were stationed up north, close to the Syrian border. Trenches were dug as fast as possible. The Syrians wasted no time in shelling us. What we couldn’t understand was how they knew our exact location. That was until we noticed that each time after the firing of our first shells, a mirror up on the hill in a village behind us was sending out signals. Our nearest water supply was in Rosh Pina. Our bedding was on the floor of the trench. There was no shade against the glaring sun. Not a soul complained. As short as the period was, many memorable incidents remain. I don’t remember what was on the menu but I do remember that I was rushed off to hospital in Rosh Pina with an acute attack of diarrhea. It turned out that I wasn’t alone. One day, way up north, in the middle of the war, a telegram was delivered to me. I had passed my final exams as a chartered accountant in South Africa. At the time, it didn’t seem to be of great importance. But in later years I found it to be of significant relevance. Up north near the Syrian border we were close to Kibbutz Maayan Baruch. With all of the action taking place, a few of us found the excuse of making our way to visit the kibbutz. School friends, comrades from the Zionist movement, founders of this wonderful kibbutz stationed almost on the Syrian border were living in trenches, protecting us. It wasn’t long before the army realized that we weren’t using artillery. These were anti-aircraft guns. Our unit was disbanded and I found myself in a camp near Haifa waiting for my next posting.

What else was there to offer? We were stationed up north, close to the Syrian border. Trenches were dug as fast as possible. The Syrians wasted no time in shelling us. What we couldn’t understand was how they knew our exact location. That was until we noticed that each time after the firing of our first shells, a mirror up on the hill in a village behind us was sending out signals. Our nearest water supply was in Rosh Pina. Our bedding was on the floor of the trench. There was no shade against the glaring sun. Not a soul complained. As short as the period was, many memorable incidents remain. I don’t remember what was on the menu but I do remember that I was rushed off to hospital in Rosh Pina with an acute attack of diarrhea. It turned out that I wasn’t alone. One day, way up north, in the middle of the war, a telegram was delivered to me. I had passed my final exams as a chartered accountant in South Africa. At the time, it didn’t seem to be of great importance. But in later years I found it to be of significant relevance. Up north near the Syrian border we were close to Kibbutz Maayan Baruch. With all of the action taking place, a few of us found the excuse of making our way to visit the kibbutz. School friends, comrades from the Zionist movement, founders of this wonderful kibbutz stationed almost on the Syrian border were living in trenches, protecting us. It wasn’t long before the army realized that we weren’t using artillery. These were anti-aircraft guns. Our unit was disbanded and I found myself in a camp near Haifa waiting for my next posting.

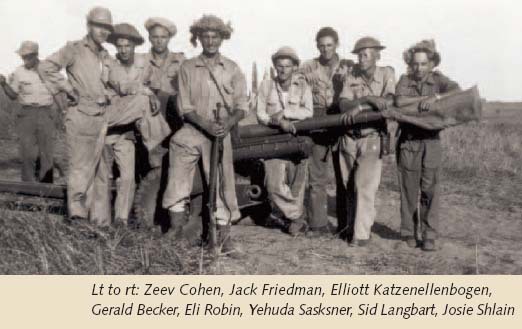

On guard duty at night, it wasn’t the enemies I feared, but the howling, hungry wolves which approached us right up to the fence. They wanted to share our rations. Within a short time I was on my way to join a unit in Sarafand. Early on, the army reached a wise decision. There wasn’t time for an ulpan, for studying Hebrew, so the units were formed with the “same-speaking” language. I found myself in The Democratic Fourth Troop, First Anti Tank 421. We had Americans, English, South Africans, Australians, Canadians and even a few New Zealanders. Our commanding officer was an American, our second in command was an Englishman, and our Sergeant Major was a South African. This was one of the most decisive steps in my life. I was greeted by my neighbor, classmate Freddy Salant. Friendships and bonding were formed many of which have lasted to this day. This was my true integration. Together, many of us followed the same path that exists to this day, not only with us, but also with our children and grandchildren. Our unit was involved in many activities: Iraq Suweidan Police Station, Faluja Hill 113. We also saw action in the north, Iraq El Manshiyah.

Others have written of the war actions. An entire book has been written on the 4th anti tank troop and its participation in the War of Independence. My tales are personal anecdotes. Shortly after joining the unit, I was called in by the medical center. Two South African doctors were in charge. They had traced my original medical enrollment and informed me that according to this I had no business to be in the army. They gave me a night to think it over. I rushed to Tel Aviv to visit a close friend from the movement. He was a psychologist. We spent most of the night yapping. The next morning I informed the doctors that I wished to remain in the army. “Fine,” they said, “but these pages will be destroyed and you can never refer to them.” This was one of the wisest and most positive decisions of my life. Each of us had a specific function. I was enrolled as welfare officer of the unit. There was one wonderful advantage. It meant that once every month I made my way to Tel Aviv to collect the pocket money, mail and parcels for all the unit.

Others have written of the war actions. An entire book has been written on the 4th anti tank troop and its participation in the War of Independence. My tales are personal anecdotes. Shortly after joining the unit, I was called in by the medical center. Two South African doctors were in charge. They had traced my original medical enrollment and informed me that according to this I had no business to be in the army. They gave me a night to think it over. I rushed to Tel Aviv to visit a close friend from the movement. He was a psychologist. We spent most of the night yapping. The next morning I informed the doctors that I wished to remain in the army. “Fine,” they said, “but these pages will be destroyed and you can never refer to them.” This was one of the wisest and most positive decisions of my life. Each of us had a specific function. I was enrolled as welfare officer of the unit. There was one wonderful advantage. It meant that once every month I made my way to Tel Aviv to collect the pocket money, mail and parcels for all the unit.

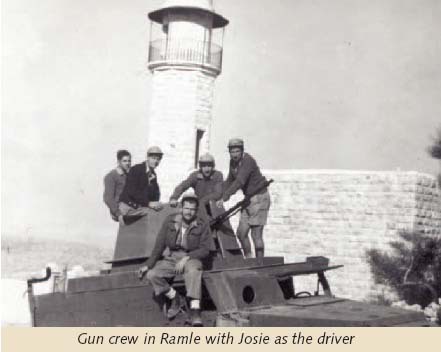

For a while, I didn’t understand why our driver always stopped at a particular army base until I realized that this was a training center for army nurses. Being a welfare officer didn’t exempt me from war action. On the contrary, as I wasn’t part of any specific team I was available, whenever there was any action, irrespective of which team it was. On one of these occasions I found myself with a team which entered Ramle. While stationed there we organized ourselves so that each day one person could have a day off. On the day that our driver had his leave, I drove our half-track the whole kilometer and a half to the army canteen. On one such day our team was changed and a group of Polish speaking soldiers took over. What were we to do? Our team sergeant would face extremely serious consequences if it was known that our team was without a driver. And so I found myself driving this heavy half-track with its guns and Polish team through the hills surrounding Jerusalem.

The stories of war actions I leave to others. As the only team with heavy guns we were in action all the time – that is, until the motor broke down. As the half-track was towed into the garage our professional driver returned. He had enjoyed the two weeks off while the motor was being repaired. Israel held out against all the Arab armies. We were winning the war and our unit was scheduled to make its way to Eilat. During our months of action, many of us realized that Israel was to be our home. How, what, which and why we didn’t know. We did know that we wished to remain in Israel. As I waved goodbye to my mates on their way to Eilat, I turned and made my way to my new duty. I had been chosen to scour the country for additional potential Anglo-Saxon immigrants and to meet with the responsible personnel to find a path for us.

The stories of war actions I leave to others. As the only team with heavy guns we were in action all the time – that is, until the motor broke down. As the half-track was towed into the garage our professional driver returned. He had enjoyed the two weeks off while the motor was being repaired. Israel held out against all the Arab armies. We were winning the war and our unit was scheduled to make its way to Eilat. During our months of action, many of us realized that Israel was to be our home. How, what, which and why we didn’t know. We did know that we wished to remain in Israel. As I waved goodbye to my mates on their way to Eilat, I turned and made my way to my new duty. I had been chosen to scour the country for additional potential Anglo-Saxon immigrants and to meet with the responsible personnel to find a path for us.

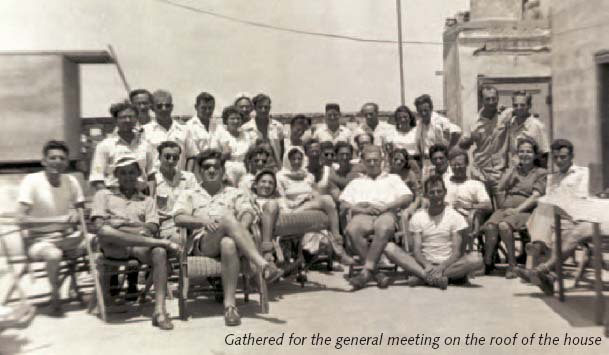

IN APRIL 1949 our unit was disbanded. All of us who were remaining in Israel prepared to make our way to our home in Sheik Munis. Our unit had set up a provisional committee, Eliezer Singer, Dave Singer and me (Joseph Shlain) to prepare the ground for the establishment of a building and agricultural cooperative. The goal was the establishment of a settlement called Beth Chever based upon cooperative principles and self labor. The settlement would be a place which could absorb aliyah from Anglo-Saxon countries and would serve as a focus of life in Israel for the Jewish communities in those countries. Two main economic spheres, which were also to be made spheres of development in Israel, were aimed at – building and agriculture. In the initial stages there would be two groups on hachshara and the fusion of the two would take place when the entire group would be on hityashvut.

We moved into our beth hachshara and held our general meetings regularly. Following are just a very few of the decisions which were made which make interesting reading in that they reflect the situation at the time.

June 6, 1949 We would receive a group ration card. This could only be had when details from each member were handed in. To be registered at the kupat cholim it is necessary for each person to have an identity card. It would probably take ten days before we could obtain these. No bigger tents were available for the families but we are applying for more tents. If no more were forthcoming it may be possible to put up hessian screens around the area of the tent to make more room.

June 6, 1949 We would receive a group ration card. This could only be had when details from each member were handed in. To be registered at the kupat cholim it is necessary for each person to have an identity card. It would probably take ten days before we could obtain these. No bigger tents were available for the families but we are applying for more tents. If no more were forthcoming it may be possible to put up hessian screens around the area of the tent to make more room.

We are going to ask once more for the water to be fixed. If nothing is done about this then we will go to the higher authority, Gurion.

Pocket money depends on whether we can afford it. At present we are spending more than we are earning.

October 26, 1949 Economy should be exercised in use of electricity. Bill for five months was 60 pounds.

Muriel said that although meals were better cooked and nicely prepared, food was insufficient in quantity. Shefayim were prepared to help us and Bolly and Harry had been sent there for tractor and lull (chicken house).

Pregnant & nursing women

The group is faced with the question of two children being born in the very near future and the opinion of chaverim was asked for on a general policy to be adopted. The custom on a moshav was for the expectant mother to be free from work entirely for two weeks before the birth and for six weeks after. The budget for clothing was 20 pounds for the initial outlay and the clothes were communal. There could be an individual budget for each child.

December 12, 1949 In view of the fact that the milk used was not pasteurized, the serving of milk to chaverim on their return from work would stop, and in future milk would only be used in hot drinks. This caution was for obvious health reasons.

December 12, 1949 In view of the fact that the milk used was not pasteurized, the serving of milk to chaverim on their return from work would stop, and in future milk would only be used in hot drinks. This caution was for obvious health reasons.

January 28, 1950 Maskiroot suggested that chaverim working out take it in turn with chaverim in house to have hot showers on alternate days, for example, Sunday, Tuesday and Thursday for chaverim working outside.

Agreed this be left to the discretion of chaverim.

A month’s supply of sugar had been used up in 10 days. Chaverim were asked to go carefully on this.

May 8, 1950 Chofesh nissuim suggested that allowances of 5 lira be granted for 4 days.

June 3, 1950 Discussion of bachurot The details are too lengthy to print in full. Sufficient to say that intensive efforts were made to attract additional females to the group.

October 21, 1950 Josie gives a brief report regarding hityashvut during the past. Josie went especially to Jerusalem to see Haartsfeldt. As usual it was very difficult to get hold of him and the very brief interview was not very helpful. However, Josie started to follow other prospects and to make enquiries.

How did we live? A few of our members were employed in the archeological excavation site of Tel Kassila. For more information refer to issue No.1, Volume 1, August 1949 in the magazine “Pioneer”. On the cover of the magazine is my school mate, the young Freddy Salant, doing his best to provide us with some income. Incidentally, our 50th anniversary was celebrated on the same grounds, today the Haaretz Museum.

How did we live? A few of our members were employed in the archeological excavation site of Tel Kassila. For more information refer to issue No.1, Volume 1, August 1949 in the magazine “Pioneer”. On the cover of the magazine is my school mate, the young Freddy Salant, doing his best to provide us with some income. Incidentally, our 50th anniversary was celebrated on the same grounds, today the Haaretz Museum.

One day, as I returned from my missions I found the ladies planning the kitchen. Where did it come from? All built in one day. I was advised, as representative/treasurer, not to enquire too much. The kitchen not only supplied our meals, it brought us in much needed extra income, as we supplied meals to those in charge of the archeological dig.

Did I say some of our ladies? Initially there were not any. We were all ex- Mahalniks. It did not take long however for many new English speaking immigrants to hear about Beth Chever and to join us. Fortunately, quite a few of them were females. Nehama, a Canadian from kibbutz Hazor met and married Les, our secretary from Wales. We even had immigrants who had escaped from Europe through China. Two of these special girls, Shoshana and Gail, married two of our Mahalniks Joe, from Canada, and Dave from South Africa. Our ex-sergeant major, Hone, informed his girl friend Rose, in South Africa, that he would only marry her if she joined him in Israel in Beth Chever. My school mate Freddy met Muriel, this gorgeous young girl from England, and wasted no time in the chiming of wedding bells. The entire families of all those mentioned, children and grandchildren, are all full blooded Israelis living in Israel, whether in the center, north or south. There were others not mentioned but I would need a book, not a magazine, to record all the tales.

What were all the rest of us to do? No problem. We discovered that the building across the river Yarkon in Tel Aviv was the home of the nurses’ training centre.

On a personal note – when Bolly Malin, an ex-paratrooper, took his mahal leave, I sent regards to my family in South Africa. He became my brother in law, marrying my sister, Sheila.

Esra recently celebrated its 30th anniversary in Kibbutz Shefayim. 60 years ago Shefayim was our nearest agricultural settlement. Some of our members trained there. Not having any spare vehicles, our trainees made their way back and forth by hitching lifts.

As recorded in the minutes, we entered the building trade. Today we need to import workers for that purpose. We were proud to help build Israel. It did not matter if you were a tradesman or if you had a university degree. Many of our members trained in Solel Boneh to become experts in the building trade.

Did I say we were destined to be an agricultural settlement? Why not use the grounds we had? But we needed to plough the soil. Fortunately, I had an uncle who owned a horse and a cart. It was brought to us and the horse pulled the plough. Now we had to return the horse and cart. To this day I tremble as I recall traveling through the main roads of Ramat Gan and Petach Tikva, with me the experienced horseman (!) guiding the wagon. Yet more was to come. One day as I returned from my missions I was greeted with great excitement by Les, our secretary. He hadn’t even waited for my opinion as treasurer. A road was to be built in front of our dwelling. As compensation we were being offered 500 Israeli lira for our vegetable crops. Actually, we earned even more. By the time the road was built we had reaped our crops. Today you travel in traffic jams on Rokach Boulevard (our vegetable garden) passing the fairgrounds of Ganei Hataarucha.

Did I say we were destined to be an agricultural settlement? Why not use the grounds we had? But we needed to plough the soil. Fortunately, I had an uncle who owned a horse and a cart. It was brought to us and the horse pulled the plough. Now we had to return the horse and cart. To this day I tremble as I recall traveling through the main roads of Ramat Gan and Petach Tikva, with me the experienced horseman (!) guiding the wagon. Yet more was to come. One day as I returned from my missions I was greeted with great excitement by Les, our secretary. He hadn’t even waited for my opinion as treasurer. A road was to be built in front of our dwelling. As compensation we were being offered 500 Israeli lira for our vegetable crops. Actually, we earned even more. By the time the road was built we had reaped our crops. Today you travel in traffic jams on Rokach Boulevard (our vegetable garden) passing the fairgrounds of Ganei Hataarucha.

The major highway to the north, the coastal road was opened while we were living at the junction. Our joker, Moshe Posner, with his ping pong ball tricks, attracted more attention than our minister Golda Meir.

Our nearest transport was the terminus of the No 4 bus at the end of Ben Yehuda Street. Quite a walk to our residence. The terrific advantage was that we could enjoy the banks of the river Yarkon, whether for a midday walk or a courting expedition in the evening. We also enjoyed the voice of Yaffa Yarkoni from across the river. There wasn’t too much noise as there was only a small wooden bridge across the river-room for no more than one vehicle at a time.

At one stage I spoke of antiquities. I still have a recording of the very first English speaking program overseas. The interviewed participants were members of Beth Chever. Despite the years that have gone by, I cannot pass this major junction without a sense of emotion. We spent only two years there, but they are years that can never ever be forgotten. It is with a sense of pride that we can look back on this brief period, realizing how many new immigrants found this house in Sheik Munison the banks of the river Yarkon as their first home in Israel.